Professional motocross racers across the world are always trying to find the upper edge on their rivals, and it’s no different in Australia. The level over the past decade has ratcheted up to such a high level here that a couple tenths of a second every lap can be the difference between taking victory – and a decent pay-check – and spending your races running mid-pack. It’s no surprise that racers are pretty motivated to try anything (legally) possible to eke out an extra couple of per cent from their bodies and machines. That’s why they attend Pro Motocross Training facilities.

While special high-performance training businesses such as the Millsaps Training Facility and the Carmichael GOAT Farm have been established for decades in the US, it’s not really a done thing in Australia. The soaring price of land, and the threat of neighbours frantically grabbing the phone at the mere suggestion of dust means the whole training facility caper hasn’t really taken off.

However, over the past six to eight years, an interesting type of hybrid training system has begun emerging here, largely spearheaded by former pro racer Ross Beaton (the older brother of Jed Beaton) in Victoria and 2012 Australian Motocross Champion Ford Dale on the Sunshine Coast. Former pro racer Nathan Crawford (00 Elite Rider Training) also has another training facility in Queensland, but his is run a little differently to what Beaton and Dale do. Rather than being based at one facility, the riders move around a network of both private and club tracks, and in contrast to, say, Aldon Baker’s full training package of riding, fitness, gym and nutrition, the two Australian programmes focus wholly and solely on technique, bike skills and simulating race-days. The off-bike and gym training is the responsibility of the racers.

How it started

For Ross Beaton, establishing the first of these training regimes in Australia almost happened by chance. An unlucky, ill-timed spate of pre-season leg injuries just before each MX Nationals season meant his senior racing career never really got going. As a result, he found himself helping Jed, whose career was just starting to blossom.

“I’d been going to the track a lot with Jed and Wilson Todd, who was living with us at the time, and I started helping them out,” recalls 32-year-old Beaton. “I’ve always got a big kick out of watching other people succeed and win races, probably more than I liked winning races myself.”

In 2016 Jed won the motocross championship while Ross was his mechanic and trainer at DPH Yamaha, then in 2017 Jed boosted to Europe to chase his MXGP dreams. Todd stayed on living at the Beatons and Ross coached him “flat out”. As Todd’s speed and results continued to build, other riders began to take notice and asked if they could join in; it wasn’t long before Beaton’s Pro Formula was born.

Ford Dale’s story has strong parallels. In 2015 he walked away from the sport following a string of injuries after claiming the 2012 title, burnt out and wanting to spend more time with his young family. While undertaking a five-year stint in the mines he was approached multiple times for coaching, but he turned the offers down, not willing to return to racing while he still had an itch to ride himself. Eventually he began going to the track with Kirk Gibbs and helped him with some on-bike training.

“That kind of got the ball rolling, where I realised I loved doing it,” Dale, now 35, says. “It grew from there pretty quickly. A few other boys jumped on board around the time of the third round of the 2021 ProMX Championship.”

Things quickly grew from there and Dale discovered a real passion for the work. The relentless work ethic he’d developed as a racer transferred across and he was able to work his butt off helping his clientele, but with a smile on his face the whole time.

While he doesn’t have an official website or name for what he does – it’s purely a word-of-mouth business – the name FD Elite seems to have stuck.

“I absolutely love what I’m doing now. I’m so passionate about helping the boys and if they put in 100%, I’ll put in 110%. The days are huge and there’s so much to do, but honestly, I can’t think of anything I’d rather do than help my group of riders reach their goals.”

Under the hood

The elite quality of regular racers on the books shows just how serious these operations are. Beaton’s core group is the larger of the two and consists of the Honda Racing riders Kyle Webster, Brodie Connolly and Alex Larwood, younger brother Jed Beaton (CDR Yamaha Monster Energy), GasGas Racing Team’s Byron Dennis, and Ryder (GYTR Yamalube Yamaha) and Kayd (WBR Yamaha) Kingsford.

Despite committing to the All Japan Nationals for factory Honda in 2024, Haruki Yokoyama will continue to be based in Victoria, while privateers Liam Andrews, Jai Constantinou, and Chandler Burns are also part of the Beaton squad. On top of that, former Australian Off-Road Champion Dan Milner (KTM Off-Road Racing Team) will also be a Pro Formula regular this year.

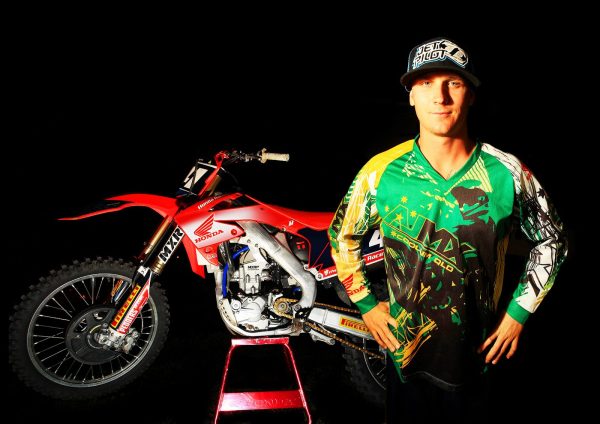

Up on the Sunshine Coast, Dale works with GasGas Racing Team’s Kirk Gibbs, Empire Kawasaki duo Luke Clout and Reid Taylor, Honda Racing’s Wilson Todd, Raceline Husqvarna Berry Sweet Racing MX2 riders Rhys Budd and Jack Mather, privateers Jet Alsop and Brock Flynn, WBR Yamaha up-and-comer Koby Hantis and Queensland state front-runners Lochie and Ricky Latimer. For Dale, the secret to success lies in finding the right balance of both rider numbers and personalities, but the main thing he looks for is work ethic.

“My number-one rule is the guys all have to train hard without me forcing them to do work, and for them all to be accountable to each other about the effort they put in,” he explains. “That’s the driving force of how they keep getting better.”

There’s also a fine line between having the right amount of riders and too many. The more racers you have out on a track, the more it changes and simulates the racing environment that they’ll experience on race day – bumps will form, ruts evolve, and corners will blow out. However, if you have too many riders it can be a struggle monitoring them all and providing the quality coaching that these racers have paid for.

“In the past I’ve probably been too generous allowing people to jump in for short periods, and at those points you can get to the 15 rider mark,” Beaton admits. “Now I’ve generally got 8-10 in the core group, which is a good number. People drop in and out as injuries happen through the season, but you need to find that sweet spot – you’re trying to run a business, budget things, and provide the machinery and resources to run the programme. That’s hard to do with six riders, but when you’re getting more than 13 it becomes unmanageable, too.”

So what does a usual day look like? Interestingly, although both guys are running their own programme, there’re plenty of similarities. Both usually beat the sun up, with Beaton taking care of any farm duties early, while Dale gets on the road to the selected track of the day. Beaton won’t be far behind, and the next two or three hours are spent prepping and watering it before the riders turn up.

The Queensland crew generally rolls in at about 9am, gears up and start riding after a bit of a rundown of what the focus is for that day, while the Victorians arrive at the track around 10am. The next few hours see both squads undertake either drills or full race simulations, complete with qualifying sessions and 25-30-minute motos, with all riders on track racing both each other and the clock. Having started earlier, the Queenslanders will knock off at 1pm, giving them the chance to then hit the gym, go for a cycle ride or make the most of the laid-back Sunshine Coast lifestyle. Beaton’s crew gear down at 2pm.

After the riders have left, both Dale and Beaton swing into action again, either undertaking some coaching with local kids, or heading to the next track on the schedule, where they’ll spend the next few hours again preparing the circuit so that it’s in prime condition for the riders. By the time their duties have wrapped up, it’s dinner time.

“My days are pinned; it’s not so much the training side, but the admin and organisation that goes into it,” explains Dale. “There’s also the relationship side of things too, as we need to do everything possible to keep the landowners and their neighbours happy.”

Both trainers have a range of tracks they have access to. Once a week they’ll use local club tracks such as Coolum or Wonthaggi, but the remaining tracks are a mixture of clay, sand, hard-pack or deep, rutted circuits. Generally speaking, they have several base tracks they call on, but they’ll also throw in another location once a week to break up the routine and keep the enthusiasm high.

Culture is everything

For Dale, the beauty of being based on the Sunny Coast is the lifestyle that comes with it, although training in the heat of summer – when the pre-season is in full swing – can be a minefield.

“Winter here is amazing and is our busiest time of year, but summer is brutal,” he explains. “It’s stinkin’ hot, humid as hell, and I have to be careful not to burn the boys out. I was one of those guys who could ride all day regardless of the conditions, but I don’t run the programme around what worked for me – it has to work for everyone so I get the best out of them. That’s not necessarily riding six days a week and burning bikes and bodies out.”

For Beaton and the Victorians summer training is perfect, but prepping and racing tracks in the middle of winter is hard work.

“Everyone gets really keen through the pre-season and that’s a peak time for us. People want to get organised and think that doing a few weeks of riding with us is going to give them the results they want for the rest of the season,” Beaton says wryly. “The weather definitely dictates the programme, though. In summer we’re usually praying for rain, but through the winter we’re praying for sun, and finding a variety of places to ride can be a challenge. This winter it was even too wet to ride at Wonthaggi at times.”

One thing that does stay consistent is the need to maintain a constant, motivated and positive culture in the group. With a lot of the riders training together off the bike, and in some situations, living under the same roof, it’s actually quite rare for issues to arise. However, when they do, both trainers say it’s best to address any niggles early and keep open communication, rather than let things simmer.

“To be honest, I haven’t had too many issues with weird dynamics, but I can tell straight away if someone’s going to work hard or not,” Dale describes. “If there are eight guys working their butts off and pushing each other, it helps the whole group, but if one guy isn’t putting in the effort, it takes away from everyone’s effort. It’s one of those things I’m really on top of, and I’m not interested in people who half-arse it.”

For Beaton, having more riders can occasionally mean more egos or people not seeing eye-to-eye.

“One of the biggest things is communication, and dealing with a range of personalities,” he elaborates. “Some people need more love than others, but if you focus too much on that person, others feel there’s favouritism, so it’s a difficult balance. Managing that, building people up from their bad days, and trying to rein in the egos when they have really good days, is a constant juggle. You don’t get points for winning training days”

Beaton admits that having his younger brother in his camp has also caused rumblings of favouritism in the past, but he says if anything, he makes a conscious effort to help Jed less, to try and counter-balance those murmurs.

“At the end of the day though, we’re brothers and our communication comes effortlessly. It’s amazing to have him home after six years racing in Europe, and I’ll always feel like I can talk to him about more things than the other guys. I think people see that communication and misconstrue it for extra attention and training, when in reality, I’ve been reluctant to help him out too much, because I’m really aware of that stigma.”

For love or money

These days every former pro or local hero is undertaking coaching schools, and for good reason. It’s a lucrative gig that provides the feel-good factor of helping the next generation, for only a few days of work a week, and they can take home a handsome pay packet. Comparing the pay hour-for-hour and the effort and investment required, the casual coaching schools win hands-down; that begs the question as to why Dale and Beaton work their arses off every day when they could be equally – if not more – financially successful if they focused on the groms.

For Ford, it comes back to what he’s passionate about: “if it was a financial decision, I’d absolutely do schools, but it’s about what I love doing. I treat my job with the same desire and passion as when I was a racer. I’m invested in it 100%. I ride the wave with those boys, but it’s what’s built in me.”

While passion plays a big part of it for Beaton, he also takes pride in the fact that he’s seeing the level of racing in Australia consistently improving every year, and is helping prepare his riders for bigger things.

“Australia is producing really good riders time and again, and I feel like that’s an attribute of what the likes of myself, Ford and Nathan Crawford are doing,” he says. “For sure, if I wanted to make a lot of money I could sit in my dozer during the week and coach kids on weekends but I just love the challenge of helping my guys become exceptional. I want to create a level that when these guys get the opportunity to spread their wings and go overseas, they’re ready for it.”

WORDS SIMON MAKKER